Memento Mori in the Ancient World · Plague, War, and the Shortness of Life

Rome, 166 CE

The smoke rose from the pyres day and night. Bodies wrapped in linen lined the streets near the Esquiline Gate, waiting their turn for the flames. The Antonine Plague had come to Rome with the legions returning from Parthia, and now it filled the city with a silence broken only by coughing and the crackle of funeral fires.

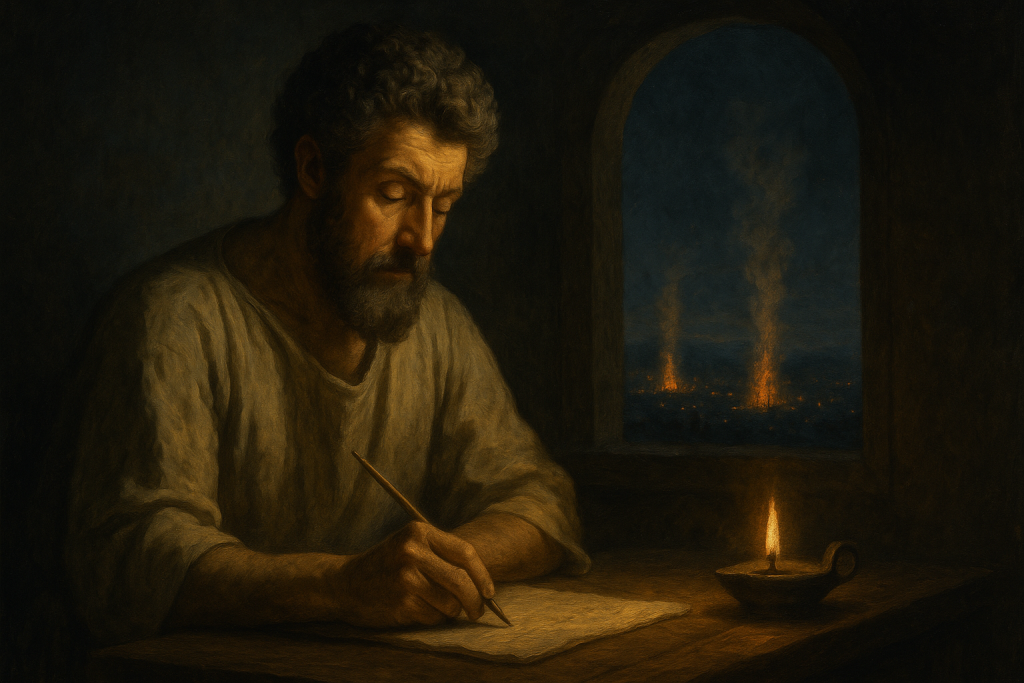

In a chamber near the Palatine, Marcus Aurelius sat at a plain wooden desk. The emperor of Rome, master of the known world, commander of legions that stretched from Britain to the Euphrates, wrote by lamplight. Around him, the machinery of empire groaned under the weight of catastrophe. The Senate met in smaller numbers each week. Whole neighborhoods stood empty. Yet his pen moved steadily across the page, recording not dispatches or decrees but reflections on how to live when death walked openly through the streets.

He wrote a single line, then paused. Outside, another pyre was being lit. The smell of burning cedar mixed with something worse. Marcus set down his pen and looked at what he had written: “You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.”

The plague would kill millions before it burned itself out. But in that moment, one man sat calmly with mortality and asked what it meant to live well in its shadow.

Death in Plain Sight

Romans did not hide from death. They built their tombs along the roads leading out of the city, stone monuments that lined the Appian Way for miles. Travelers heading south from Rome walked between rows of the dead, reading epitaphs that called out from marble: “I was not. I was. I am not. I do not care.” The deceased spoke directly to the living, reminding them that the journey ended for everyone.

In the city itself, death was public theater. Gladiators fought in packed arenas, and the crowd watched men die for entertainment. Criminals were executed in the Forum, their bodies left on display. When a great man died, his funeral procession wound through the streets with actors wearing the death masks of his ancestors, a parade of the family dead walking one last time through Rome.

The triumph, that supreme honor given to victorious generals, carried its own reminder. As the conquering commander rode through cheering crowds in his gilded chariot, crowned with laurel and draped in purple, a slave stood behind him. The slave’s only task was to whisper in the general’s ear throughout the procession: “Remember you are mortal.” Even at the peak of glory, with Rome prostrate in admiration, the shadow was there.

Death masks hung in the atriums of noble houses. Wax faces of the dead stared from the walls, ancestors watching their descendants with hollow eyes. A Roman child grew up surrounded by these imagines, learning early that the living were temporary and the dead were permanent fixtures of the home.

This was not morbidity. It was realism. The Romans built their world on the certainty that everything ended, and they refused to pretend otherwise.

When Plague Came

The sickness arrived without warning. Soldiers from the eastern campaigns brought it back in their blood. It started with fever and thirst, then came the cough that never stopped. Pustules covered the skin. Some victims died within days. Others lingered for weeks, their bodies failing piece by piece.

Marcus Aurelius had ruled for five years when the plague struck. He was a man trained in philosophy, a student of Stoic teachers who had taught him that death was nothing to fear. Now the teaching faced its test. The disease took senators, soldiers, slaves. It did not discriminate. Each morning brought news of who had fallen in the night.

The emperor could have fled to a country villa, away from the contagion. Instead he remained in Rome, overseeing the crisis, making decisions about grain supply and funeral procedures. And at night, he wrote. His private journal, never meant for publication, became the record of a man watching an empire die while trying to determine how to live.

He wrote of people panicking over trivial losses while their lives evaporated. He reminded himself that fever was no more or less natural than health, that death was simply a process, like digestion or sleep. The words were not cold. They were the thoughts of someone trying to find solid ground while the world dissolved.

One passage returned again and again to the theme: life is brief. Not as complaint, but as fact. A human span was nothing against the sweep of time. Empires rose and fell. The plague itself would pass. Everything was smoke and shadow, here for a moment and then gone. The only question that mattered was what to do with the moment while it lasted.

On the streets below his window, the pyres burned through the night. Marcus finished writing and closed the journal. There were decisions to make, a city to govern, a crisis to navigate. Death was everywhere, which meant there was no time to waste on anything less than what truly mattered.

The Soldier’s Calculus

Three generations earlier, Roman legionaries had marched into the Teutoburg Forest. Three legions, XVII, XVIII, and XIX, vanished in the German woods. Fifteen thousand men, ambushed and slaughtered in a campaign that should have been routine. When word reached Rome, Augustus was said to have wandered his palace for days, beating his head against the walls and crying out, “Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!”

But the legions were gone. And the soldiers who marched after them knew they might not return either.

Roman military culture was built on this knowledge. Every soldier swore an oath that included the acceptance of death. They trained with real weapons, and training casualties were common. Before battle, commanders reminded their men that courage came from accepting the worst outcome. A soldier who had already made peace with death fought differently than one who still hoped to escape it.

Centurions drove this lesson home with brutal efficiency. Hesitation in combat meant death for the entire unit. The Romans won battles not through superior individual skill but through collective discipline, and discipline required every man to act as if his life was already forfeit. The legion became a single organism because each soldier had surrendered personal survival to the whole.

This was not fanaticism. It was calculation. A man convinced he would survive fought cautiously, protecting himself. A man who accepted death as inevitable fought with clear purpose. The Romans understood that the fear of death made men weak, while acceptance of it made them unbreakable.

Veterans bore scars like tallies of near misses. They had seen friends die in ambushes, from infected wounds, from disease in winter camps. Yet they re-enlisted, marching out again with the knowledge that any campaign might be the last. Their willingness came not from ignorance of risk but from something harder: the conviction that death would come regardless, and the only choice was whether to meet it well or badly.

The Practice of Dying

Seneca was sixty-seven when Nero’s soldiers came for him. The emperor had decided his old tutor was involved in a conspiracy, and the sentence was death. Seneca received the news without surprise. He had spent decades writing about mortality, preparing himself for this moment. When it arrived, he faced it the way he had taught others to face it—calmly, as one fulfills an appointment long scheduled.

This was the Stoic method. Not to ignore death or suppress fear of it, but to rehearse it daily until familiarity replaced terror. Seneca had written to his friend Lucilius that every night before sleep, a man should imagine his life ending. Not as morbid fantasy but as mental preparation. In his letters, he returned constantly to the same theme: we are dying from the moment we are born, losing time with every breath, and the only wisdom is to spend what remains without waste.

The exercise had a name—premeditatio malorum, the premeditation of evils. Students of philosophy practiced imagining loss: the death of loved ones, the collapse of fortune, their own final moments. The goal was not pessimism but inoculation. If the mind had already faced the worst in advance, the actual event lost its power to shatter composure.

Epictetus, teaching in his small school decades later, drove the point home to his students with harsher words. He told them to kiss their children goodnight and think silently, “Tomorrow you may be dead.” Not to spread gloom but to strip away illusion. The child was not a permanent possession but a temporary gift, on loan from nature and subject to return at any moment. Recognizing this truth did not make a father love less. It made him love more carefully, knowing the time was limited.

The practice shaped how Stoics lived. If death could come this afternoon, what use was grudge-holding? What point in hoarding wealth or chasing status? The meditation did not make them reckless. It made them precise. They learned to distinguish between what mattered and what merely seemed to matter. The things that consumed most people—reputation, comfort, security—revealed themselves as trivial when held against mortality. What remained were the things death could not touch: integrity, kindness, courage, the choice to act rightly in the time available.

Marcus Aurelius, writing during the plague years, condensed the practice into stark reminders. Think of yourself as already dead, he wrote. The years after this moment are borrowed time. Use them as a dead man given a second chance would use them—with nothing left to lose and no reason to hold back.

What the Certainty Changed

The meditation on death had effects the ancients did not bother to hide. It made them generous in a specific way. A man who truly believed his wealth meant nothing at the grave gave it away more freely. Seneca, one of the richest men in Rome, wrote that money should flow through one’s hands like water, benefiting others on its way. Hoarding it was the act of someone who believed he would live forever, a delusion death would eventually correct.

It made them forgiving. Holding grudges was the luxury of people who imagined they had unlimited time to nurse resentments. But if life could end tomorrow, what purpose did anger serve? Better to settle disputes quickly, let go of slights, and spend the remaining hours without the weight of bitterness. Marcus Aurelius reminded himself that the person who wronged him today might be dead tomorrow, or he might be, and either way the grudge would die unresolved.

It made them brave in a particular sense—not fearless, but willing. The soldier who marched knowing he might not return was already free of the paralysis that came from trying to guarantee safety. The Stoic who had rehearsed his own death daily did not become immune to fear, but he learned to act despite it. Fear lost its veto over action when survival was not the highest priority.

Most of all, it made them present. This was the strangest effect and the hardest to counterfeit. The Romans who lived with death in plain sight did not drift through their days waiting for life to start later. They understood that later was a fiction. This conversation, this meal, this walk through the Forum—these were not preparation for something more important. They were life itself, and they were ending even as they happened.

Seneca wrote that people waste their lives preparing to live. They spend years accumulating resources, building security, arranging circumstances, always with the thought that the real living would begin once everything was in place. But the real living was happening during the preparation, and most people missed it. Only when death became visible did the illusion break. Then, too late, they saw that every moment had been the thing itself, not a rehearsal.

The Romans who practiced memento mori were trying to skip the final realization and live from the start as if death were already visible. It was not a philosophy of despair. It was a method for refusing to sleepwalk through the only life they would get.

The Weight of Clarity

The plague years finally ended. Marcus Aurelius did not live to see Rome fully recovered. He died in 180 CE, likely from the same disease he had spent years trying to contain. His private journal survived, copied by someone who recognized its value. In those pages, the emperor who ruled the world returned again and again to the same truth: death strips away pretense and shows what matters.

The Romans understood something that comfort obscures. When death is distant, life becomes negotiable. People compromise, delay, drift. They hoard time as if it were infinite and spend it on trivialities as if nothing would ever be required of them. But when death stands in plain sight—whether from plague or war or the simple certainty of age—everything clarifies. The small anxieties reveal themselves as wastes of attention. The hesitations appear as cowardice. The delays look like theft from a diminishing account.

This was not meant to make life grim. It was meant to make it vivid. The Stoics who meditated on mortality did not become gloomy philosophers shuffling toward the grave. They became men who noticed the world more sharply, loved more deliberately, and acted with less reservation. They had looked at the worst outcome and found it survivable, which freed them to stop protecting themselves and start living fully in the time they had.

Along the Appian Way, the tombs still speak to travelers. The stone inscriptions carry the same message they carried two thousand years ago: the dead are not concerned with the things that consume the living. What seemed urgent yesterday means nothing today. What appeared permanent proved temporary. The only lasting question is whether the life was spent on things that deserved it.

Marcus Aurelius closed his journal for the last time knowing he had done what he could with what he had. The empire would continue or collapse. His writings would be read or forgotten. None of it mattered as much as the choice he had made each day—to live as someone who knew the hour was late and refused to waste it.

In Utica centuries before, Cato had faced his mortality and chosen integrity. In Rome during the plague, Marcus did the same. The circumstances differed, but the clarity was identical. Death, when faced directly, becomes not an enemy but a teacher. It shows what can be lost and what cannot. And in that showing, it reveals the only freedom that matters: the choice to live well in the time that remains, however brief that time may be.